Speaker: Margaret Parkes

Venue: Plettenberg Bay Angling Club.

Date: 13 September 2009

Whaling was an industry centred in Plettenberg Bay for many years. Well-known names associated with its earliest days in the 19th century were firstly that of Captain Sinclair in the 1830s, and later, Cornelis Watson in partnership with Percy Toplis before the building of the whaling station on Beacon Island. Toplis held the lease of the Island before the Norwegians took over. In July 1899 Watson was lost at sea with his boat and crew of five in pursuit of a very large right whale west of Plettenberg Bay. He and his crew, the whale and the boat were never found. Then there was Holmes, who caught a whale in October 1900, valued it at £350 and in true fisherman style said ‘the one that got away would have been valued at twice the price!’

With these reports it was only natural that whaling companies should show an interest in the southern Cape, and in 1908 the Select Committee on Waste Lands recommended the granting of a lease to Southern Whaling Company on part of the Crown Land from the mouth of the Piesang River to Seal Point, the area to be not more than ten morgen, for a Whaling Station for the manufacture of products derived from whales. The rent was to be 2/6d per morgen, the rent for the right to erect a jetty to be £1 per annum, with the lease not to exceed 25 years. In 1909 the Whaling Company Started their whaling business with no shore base, i.e. from three whaling operations afloat working from three whaling steamers with about seventy men. Thesen and Co. of Knysna were the South African agents of the new Company. However, in the following year, 1910, a representative of the Whaling Company decided not to establish the Whaling Station on land at all, owing to the Nature of the roadstead rending whaling difficult with its poor anchorage.

The next we hear of Mr. Thesen is when he was acting once again as an Agent for the Hans Ellefsen Whaling Co. Ltd., registered in Cape Town, having addressed both the Knysna Municipal and Divisional Councils in 1911 on the advantages of erecting a whaling station on either the south of Paarden Island, now known as Thesen Island, or on the Brenton shore. Without much research they were in favour of the move. Not so the townsfolk of Knysna. A large public meeting, the largest yet to be held in the Knysna Town Hall, was called by the Mayor, Mr. T. G. Horn, when Mr. Thesen was asked to address the meeting.

Dr. George Marr also addressed the meeting, having carried out research locally and having contacted the necessary authorities at Saldanha Bay, Durban and Mossel Bay for further advice and opinions, all whom were against the move due to, not only the unpleasant smells which the industry would generate but also the damage it would cause to the tourist industry, sport, sailing and swimming, as well as its effects on the local fishing industry which formed the livelihood of the poorer townsfolk and district. There was an audience of about 260 at the meeting, but only 5 voted in favour, the remainder being firmly against the proposal. To further confirm the Town’s disapproval, a signed petition was sent to Minister of Lands, who in reply turned down the proposal officially.

In the George & Knysna Herald of 22 May 1912 there was a Notice by the Department of Lands stating that J.E. Harrison of “Balmoral”, near Millwood, had applied to lease a site in the vicinity of Seal Point, facing Plettenberg Bay, for the establishment of a Whaling Station for the manufacture of “products derived from whales”, and signed by G.H. Hughes, Acting Secretary of the Department of Lands, but no more was heard about it. In June 1912, the Plettenberg Bay locals heard of two Whaling Companies intending to start operations there, – one at the mouth of the Keurbooms River on the site of the Old Residency. To this, Mr. H.D. Van Huysteen and those living on the banks of the Keurbooms River objected strongly, again because of the smells, and they said also, ‘because the oil and scum would flow up the river and settle on their grazing lands.’

It was only natural when the next whaling company was to come to this area that Mr. Charles Thesen once again acting as Agent, had to look elsewhere than Knysna for the venture. In 1895, whalebone was going at £1,300 a ton, and double that price in scarce whale years. Two right whales caught in Plettenberg Bay in 1895 gave 1,752 gallons of oil and 769 lbs of whalebone, which made it an attractive industry.

In the town of Haugesund on the south-west coast of Norway there had been a flourishing sardine industry, but over-fishing led to its decline and a prominent man in the industry, Hakon Magne Waldemar Wrangell and others, invested in whaling instead off the Norwegian coast and off Iceland where Wrangell was later to have two stations. But as the whale population in these waters declined and with stringent controls in the whaling industry increasing, Wrangell decided to look elsewhere to Spain and Angola. These proved to be not profitable, so he moved his operations to South Africa because of the growth of the industry in the East.

In 1912 the Norwegians thought it desirable to form a whaling company with a capital of 1.3 million Nowegian kroner to counteract the Chinese. Wrangell’s dream in 1911, was to build the biggest and most modern Whaling Company in the world, choosing Plettenberg Bay, in which he invested a great deal of money. In 1913 the Whaling Station was erected on Beacon Island, Plettenberg Bay, and it was the largest station in Africa with seven of the largest whalers operated by experienced crews. The seven new whalers were built at the shipyard of Akers Mekaniske Verksted in Christiana, Norway, at a cost of 800.000 Kr. delivered to Africa. The buildings on Beacon Island, including the equipment, cost 600.000 Kr., and were placed under the supervision of Captain Jacob Odland. Wrangell, resident of Haugesund, then became the owner of the Harald Haarfagre Company of Beacon Island. His life was a real “rags to riches” story.

Who was this Wrangell? He was born on 2 January 1859, the illegitimate male child of Cecilie Tjaeradsen, his father’s name was Hans Wrangell. The baby was only two years’ old when his mother, a housemaid, sent him to her parents in Stavanger to be cared for, where he attended the local school for the underprivileged. He was a clever boy, coming first in his classes. His mother had in the meantime married a shopkeeper. Wrangell left school at the age of fifteen and at first took menial jobs such as selling cheap cigars to sailors and working for a tailor as his delivery boy until the tailor died in 1874. Wrangell then returned to help his widowed mother in her shop for two years. When she sold her shop, Wrangell went to work for the shipping company of R.G. Hagland for three years when he opened his own general dealer’s shop and started selling provisions to ships. After two years, in 1880, he started his own Ships’ Chandlers Company selling provisions to the local shipping companies. In a few years he had the biggest ships’ chandlers company in Haugesund and in 1900 owned two whaling stations, Hekla and Talkna, north west of Norway in Iceland. The third, in Plettenberg Bay, South Africa, was to be called the Harald Haarfagre Whaling Company named after an early, former king of Haugesund who reputably united the many small kingdoms in Norway under one throne in about the 10th Century. Harald Haarfagre was regarded by staunch Nationalists like Wrangell as a symbol of the independence from Sweden and Denmark they strove for. His grave is situated just north of Haugesund and is often the site of a gathering place for festivities.

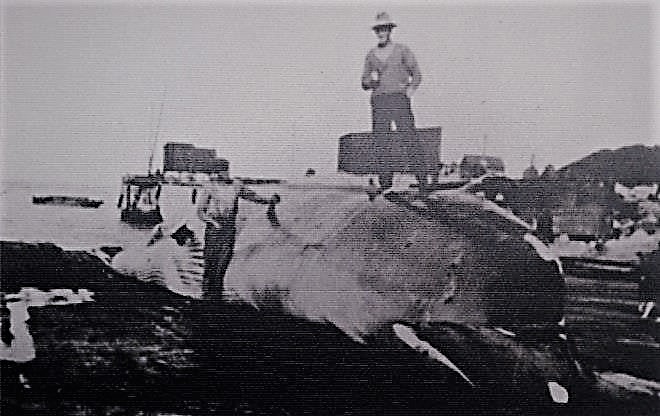

To start his South African venture, Wrangell acquired the lease of Beacon Island, and by February 1913 the greater part of the Island had been flattened, leaving the rocky centre dome intact on which the Manager’s home was to be built and where the historical Beacon stood with the exact longitude and latitude figures engraved on it, (which was replaced in March 1881 by Harbour Master John Fisher Sewell.) The building materials for the wooden pre-fabs built in Norwegian style with overlapping boards and decorated fascia boards came out from Norway on a 60-day voyage on the ss Sigrun in 1913. the 4000-ton cargo was transshipped from the ss Sigrum to the beach by means of lighters brought round from Port Elizabeth. Between 50 – 60 men were employed on the task plus Coloured labourers carrying the contents of the lighters to higher ground. Mid-year, in the winter, there was a little bit of trouble, as you could well expect, when the labourers objected having to stand in the icy sea unloading coal etc. from the lighters. There were mishaps too when one lighter sank complete with cargo, and another broke its back on the beach. On the beach were iron tuns, trying-out pots, boilers weighing as much as 17 tons, plus Norwegian wood ready to be assembled for the factory complex.

The whaling complex consisted of the factory on the north side of the island with a cement slipway running into the water on which the whales were dragged up to the factory. (The slipway was still visible when we used to stay at the hotel in the 1940s and ’50s.) The manager’s house stood in the centre of the Island with the wooden single-storeyed crews’ quarters on the west side. The seven whalers that were to operate in conjunction with the factory, came out in 1913. They were newly-built specifically for operations out of Plettenberg Bay by the Aker Mechanical Shipyard of Christiana at a cost of 800,000 Kr, and the cost of the whaling station buildings was 600,000 Kr.

The first whaler to arrive in Knysna for coal and water en route to Plettenberg Bay was the SS Plettenberg, built in 1912, to be followed on 4 May 1913 at Knysna by the Zitzikamma, Captain W.Andersen; the Formosa, Captain K. Jacobsen; the Bitou, Captain J. Jacobsen; all having taken a 45-day voyage out, calling at four points for coal etc. en route. The arrival at Knysna jetty of the four whalers plus the Thesen-owned SS Agnar which was lying alongside the jetty, and the little SS Clara which operated between Storms River mouth and Knysna, must have given the Knysna harbour area the impression of really bustling port.

These four whalers were followed by three more, the Piesang, Captain Svendsen on 15 May 1913; the Goukamma, Captain Johan Langeland; and the Knysna, Captain O. Olsen. The whalers were to become frequent visitors as they went to Knysna not only for water and coal but also to lie off the sand bank to be cleaned and painted, and in the off-season to lie off Brenton shore, for which permission had to be obtained from the local Port Office.

In the first season in 1913, only 211 whales were caught with 8,800 barrels of oil produced 4,000 bags of guano, leaving a debit of 6 – 7000 Kr. The 1914 season was a busy one with ships calling in to take out cargo, and others calling in with cargo. In March, ss Haugarland, with Captain O.C. Mathiesen at the helm, called in to collect cargo for Europe, and in the same month the chartered vessel from Norway, the ss Lesseps took on a cargo of whale products valued @ £19,925 for Europe. In June, 160 whales were taken, and the ss Lesseps took away 7000 barrels of oil. In July it was reported that 220 whales had been taken for the season, and in the following month the ss Lesseps called in again taking away whale products to the value of £20,377. In the following year, in January 1915, the SS Lesseps took away whale products valued at £18,125.

In August 1915 it was reported that two sperm whales were taken and in November it was reported that only 9,800 barrels of oil for the whole season were exported. By September 1916, 170 whales had been taken up until this date, and the production of oil had dropped to 8,200 barrels. Also, charter costs for steamers to take barrels of oil to Norway had increased during WW1 from K500 to K1900 per month. The Company then decided to make this year their last, and to close down the swhaling Station.

Besides these steamers collecting barrels of whale oil and other whale products, there were others of the Thesen Steamship Co. bringing coal from Durban, the ss Karatara calling in February, May and June 1914, and the ss Agnar shipping 4,150 bags of whale guano and bonemeal out from the Bay in March 1916. Captain Abrahamson of the 100 ton ss Elida was also taking coal cargo to Plett. returning from Plett. with oil to Cape Town.

Wrangell’s dream was not without its nightmares. The first disaster was that of the Manager, Captain Jacob Odland in April 1913 while he and a group of friends were travelling to Knysna in his smart red car of 20 – 22HP when someone smelled burning of metal as they descended the Nekkies into Knysna.. Odland immediately drew over to the side of the road and punctured the petrol tank to prevent an explosion. But despite this, the car was badly damaged except for the 4-cylinder engine. All that remained that was useable was the engine which Odland sold to Leonard Thesen and H. Noren for £20. The engine was later mounted onto a flatbed truck of the South Western Railway, which ran from Knysna into the forest, used by Thesen and Co. to transport their men from Brackenhill to Paarden Island in Knysna for the building of their new saw-\mill.

Mishaps generally come in threes – the next disaster occurred when Captain Waage of the Plettenberg was injured while trying to harpoon a whale just south of Plett. Two harpoons had already been fired but did not kill the whale quickly enough for the Captain’s liking, so he fired a third harpoon without taking all the necessary precautions and the harpoon glanced off the whale carrying the line upwards catching the Captain on his left side, injuring his left leg, and coming under his left arm which was broken in two places and even caused the loss of one of his eyes. The plucky skipper first landed the whale at Plett before proceeding the next day by sea to Knysna for medical treatment. Later that week, after the Captain had been successfully operated on, and whale oil having been sent to Europe, the next disaster to occur was the fire on 15 July 1914 when the large double-storeyed building containing the machinery and boilers for rendering the flesh and offal of the whales into animal food and fertiliser, caught alight and was almost totally destroyed. Much of the building was of course, built of wood. However, by using hoses they were able to save the working platform, the hauling engines and the blubber boiling building on the west side. The dynamo and electric generator were also destroyed, placing the loss at £7,200. By February in the following year, much of the damage had been repaired, but before the factory came into operation again, the carcasses of the whales had to be dumped at sea, which further increased the Company’s losses.

The next disaster to occur was the wreck of the 40-ton whaler, the Piesang, on the bar in the Knysna Heads at 10 a.m. on 1 September 1914. The whaler, under the command of Sivert Svendsen with a crew of ten men, was loaded with a water ballast, capsized as she entered the Heads. The whaler was caught by a huge roller which mounted suddenly and hurled the Piesang nearly over on her starboard side, the vessel then righted herself when the same roller turned her over again on her right side submerging her utterly in the process. It all happened in a few seconds. It was thought by some that the lifeboats may have shipped water and been part of the cause. The tragedy was witnessed by the pilot at the Heads who immediately raised the ball on the signal mast to prevent the other two whalers from going out, and the sailing ship, Westphalen, loaded with creosote for the government railway sleeper factory, from coming in. Conning Benn, the Signalman, witnessed the tragedy and rushed down to the shore to offer assistance. The Captain was found lifeless, floating face down in the water, and only five members of the ten-man crew were saved. The wreck lay blocking the mouth of the harbour, the Durban tug Sir John was then sent for and the Captain tried to lift the stricken Peisang with a hawser – but it gave away. It was then decided to blast the wreck. After this was carried out, the body of the chief engineer Karl Ivar Hogberg of Haugesund and another engineer were released, plus that of the steward, Gabrielson. The body of Petrus Ohrn was found at The Heads and that of a sailor, at Coney Glen. The bodies of all five men were buried in the Anglican cemetery opposite the hospital in Knysna. One of the survivors, Gunner Severin Jacobson from Aucklandshamn later became a famous gunner in the Haugesund area.

I had the privilege last year of meeting the grandson Helge Kallelund, of the engineer Karl Hogberg of the Piesang, who came out to Knysna to view the site of the disaster and to learn more about the wreck. Helge told me that his grandfather had nine children and he joined the whaling fleet out here as they were offered double pay. A temptation that anyone with a large family as Hogberg had, would take, and it is a tragedy that it had to end in disaster.

With World War 1 making shipping risky and difficult and the fact that in 1916 only 8,200 barrels of oil was produced, it was decided to close the factory down and sell the machinery etc. to the Union Whaling Company of Durban. The six remaining whalers were disposed of in 1917 to the French Marine, delivered to Port Said and used as patrol boats. All of them had their names changed immediately to French names: the SS Plettenberg became the Rouget; the Formosa, the Congre; the Knysna, the Dauphine III; the Bitou, the Sardine; the Goukamma, the Sole; and the Zitzikamma,the Raie III.

After the sale of the whaling company, the Beacon Island was advertised by the Department of Lands to be leased. The lease was auctioned on the stoep of the Knysna Magistrate’s Court. The first Lessee was Mr. Thomas Herbert Hopwood and his wife Annie, nee Newdigate, of Forest Hall. Tom Hopwood joined the Crown Mines after the Boer War where he was employed as a Shift Boss. On 2 December 1916 he and four other men came to the rescue of a miner with three African assistant miners who had been badly gassed underground. For this brave deed he and the other men were each presented with a medal and an engraved gold watch for bravery.

Tom arrived in Plettenberg Bay in 1920 and in partnership with a Mr. and Mrs. H.I. Plaskett ran the Beacon Islet Residential Hotel. The partnership was dissolved in February 1922. The Hopwoods used the Norwegian-built ex-Whaling Station Manager’s home – a double-storeyed house consisting of a large dining room, lounge, six bedrooms plus what had been the crews’ quarters – a long single storeyed building on the west side of the Island. We, as children, went there in the 1930s with our parents and I can vaguely remember sleeping there with our Nanny, Miss Stevenson. About twenty boarders could be accommodated there but what most folk remember is the flush toilet, – and flush it was! The toilet was placed on two girders which spanned a gulley in the rocks known as ‘doodval’ with duckboards on the girders leading to the toilet. The other memory is of the pool in the rocks on the south east corner of the Island known as Mermaids’, or Eve’s Pool, in which we used to swim.

My father recalled that the food was very plain as the Hopwoods often ran short of things, so guests would bring a certain amount of their own rations to augment the menu. Father said that if they ran short of rations Mrs. Hopwood would apologise and give a kiss! In 1926 when the lease came up for renewal, the Hopwoods took up a further 5-year lease at £165 p.a. with an advance of 100 guineas. They ran it until 1931 when Mrs. Rosina Parkes – no relation – took it over.

I was shown the Hopwoods’ Visitors Book which made most interesting reading. The first entry, the 22nd September 1921, was that of then recently retired ex Civil Commissioner, Colonel Calcott Stevens and Mrs. Stevens; in 1922, other folk of importance were Bishop and Mrs. Sidwell of George and Magistrate and Mrs. Strong. In 1924, the well-known deaf-and-dumb artist, Harold Boyes, and George Cearn directly from Nairobi who was to play so important a rôle in the development of Leisure Isle, were visitors, and in 1930 the Minister of Railways and Harbours, Charles Malan. Signatures of residents of the surrounding areas were those of the Thesen, Newdigates, Dumbletons, Metelerkamps, and my parents – (five months after I was born.) It is interesting that some of the names are still associated with Plettenberg Bay. In 1932 Mr. and Mrs. Mackie Niven of Sundays River, 1930, the Wheeldons of Grahamstown, many visits by the Diceys of Orchard and Wolsley from 1924 onwards; R. Tredgold in 1926 and almost a month’s stay by Owen Grant of the Wilderness in January 1926, followed by further short visits. It was Mr. Grant who was later to purchase Beacon Island in 1938. Other visitors came from Johannesburg, Bulawayo, Bloemfontein, Cape Town, etc. at the same times as running the hotel, in 1922 Tom Hopwood had a fish smoking business called The Pioneer Fish Curing Works where the Why Not restaurant was. One of their employees was Angus McCallum.

There was a very rickety old wooden bridge from the mainland to the hotel and you had to leave your car on the mainland and have your luggage carried over the sand when you came there on holiday. The newspaper in 1927 referred to ‘a unique and pretentious bridge constructed over the river to the island’ but my memories in the 1930’s were of being quite afraid of crossing on it.

The last entry in the Visitors’ Book is of 25 May 1932 when the Hopwoods left the hotel and retired to their farm Ashlands at The Crags on land that Mrs. Hopwood had inherited from her father, W. H. Newdigate. It was later owned by Brigadier Hansen. Tom Hopwood died in June 1934, aged 64 and Anne followed him later in 1941, aged 83. Here they are both remembered by a street name after them. On their departure from the hotel it was taken over by Mrs. Rosina, Elizabeth Muller Parkes, born Raubenheimer. Her husband, originally from Scotland, had died earlier and Mrs. Parkes came originally to this district as a nurse during the 1918 ‘flu epidemic. On the death of her only daughter she decided to take over the hotel in 1932, making a few small improvements, and running the hotel, as Father said, very efficiently.

Mrs. Parkes left the Beacon Islet in 1936 to purchase and rebuild part of the old Thesen holiday home – “The Look Out” advertised “For Sale or To Let”. This she ran successfully as the Look Out Hotel on the site now occupied by the Plettenberg Hotel. Mrs. Parkes died in Plettenberg Bay on 15 April 1952 aged 71.

The Island was then untenanted for three years when an advertisement appeared in the Government Gazette of 9 September 1938 for the sale by the Department of Lands of the Island of 1.5604 morgen and Piesang River mouth of 79,211 sq. ft. at the purchase price of £1,500. Conditions of sale were that the purchaser was required to demolish all structures on Beacon Islet within six months and to erect a new hotel within five years, and the total cost of the hotel building, outbuildings and bridge or causeway crossing the river, plant for water supply, sewage and lightning to be not less than £12,500. The inscribed Admiralty Beacon was to be protected, and no building of any description would be allowed at Piesang River mouth. Further regulations stated re: access, water from the springs near the Signal Station, and sewerage.

Owen Grant purchased the Island, part of the attraction being that the National Road from Durban to Cape Town was about to begin construction, and he thought that with Plettenberg Bay’s lovely beaches so close to the road that it was destined to become a prime tourist attraction. Tenders were called for in August 1939 by Grant for the purchase and demolition of the Norwegian buildings. On the formation of the company Beacon Islet (Pty.) Ltd. Grant became the owner of the land from the Island to near Robberg, which later was acquired by the General Mining Company. Grant included this land in the new Company for £8,000 with the cost of the purchase of the Beacon Island, the buildings of the hotel, plus the land, the Company’s capital was £75,000. At a meeting held with the government’s representative, Plettenberg Bay’s residents and Grant, it was decided that a path of 5ft. above high tide right round the Island would be reserved for all time for the fishing community.

Grant had the land along the Robberg Beach surveyed and laid out in plots of half an acre, roads were made and the plots were put up for sale at the upset of £200 – 300 per plot. Father bought one just round the corner as you drive along ‘Millionaire’s mile’ and had it levelled, as did Dr. Fritz Leuner in the adjoining plot. We said to Father – “if you build there, we will get on our bicycles and ride into Knysna!” Father sold this plot shortly afterwards for £600!

The architects of Oudtshoorn, Messrs. Simpson & Bridgman, were engaged to draw up the plans for a new hotel which was to resemble the upper deck of a ship. The hotel was to accommodate 150 guests with a square bedroom block of 3 floors, all bedrooms to face outwards for the view built in 1939. The social area of the hotel was single-storeyed on the north west corner of the Island with the anglers or fishermens’ lounge to have a stone fireplace to the right of the entrance. Opposite was the reception area. The hotel had an open square grassed courtyard in the centre with an atmospheric old iron whale blubber pot standing on the grass. The childrens’ dining room was on the left of the courtyard and the large dining room faced east with seating for 200. The large lounge with a large stone fireplace, was alongside and to the south of the dining room. I will always remember the trouble they had with the steel windows rusting badly being so close to the sea and rocks. A lovely situation to sit in and look out upon the sea, but it brought its difficulties. As with the Whaling Station, some of the building material was delivered by sea by the 172 ton ss Chub bringing 3 full cargoes of timber and other building necessities delivered to Knysna and brought over to Plett by truck.

Grant had his own generator, or ‘power station’ – if one could call it that, which was situated on the north-west corner of the entrance. My other memory is of the red ‘stoep’ polished passages and steps leading up to the bedroom block. He built a causeway across the Piesang River with a hard core road leading to the hotel, completed in 1939 – an ambitious undertaking, – as well as a nine-hole golf course constructed in the valley as well, west of the Robberg beach dunes. The course started from the banks of the Piesang River and about 300 yards from the door of the hotel. It was designed by Dr. Charles Murray and constructed by Mr. F.E. Knapp.

In February 1940 Owen Grant advertised that as the hotel was expected to open 1 December 1940, local farmers who were interested in supplying the hotel with fresh produce could apply for schedules of what was required. My father and Owen Grant built their hotels simultaneously. The Royal Hotel was opened in Knysna by Charles Thesen on 1 December 1939 just after War had been declared. As the tourist trade began to suffer as a result Grant advertised special rates to attract visitors:

Friday Dinner to Monday breakfast – now £1.10.0 (was £2.2.6d.)

Friday Dinner to after Supper Sunday – now £1.5.0 (originally £1.13.6d)

Saturday Dinner to after Supper Sunday – 15/- (originally 18/6d.)

When the German army had reached Egypt in 1942 the British Military authorities decided to evacuate the families of civil and military personnel holding British passports resident in Egypt to South Africa. Owen Grant and Father made contact with the South African Military authorities and Mr. Kemph of the Evacuee organisation offering accommodation in their hotels for the evacuees. The Royal Hotel in Knysna was allotted 60 officers’ wives – a mixture of Greek, French, Maltese and Eastern Mediterranean nationals. The first batch of 130 evacuees arrived in Knysna in July 1942 and were divided between the hotels in Knysna and Plettenberg Bay of which 48 were sent to Plettenberg Bay. The second batch of 44 women and 41 children arrived at the end of July, of which 71 were sent to Beacon Island, Plettenberg Bay. Those who were assigned to Beacon Island were a rather motley crowd who very soon aired their dissatisfaction at the lack of facilities with only one shop, no cinemas and all the urban facilities that a town has to offer, in spite of the fact that the area had been inspected and reported on beforehand! Fortunately the evacuees did not stay long and were moved to perhaps brighter lights elsewhere. In September 1942 Owen Grant advertised in the newspaper that the hotel was once more open to the public.\Hugh Owen Bruce Grant, founder, and one of the many owners of the Beacon Island hotel, was born in Finchley, London, England on 30 June, 1883 and trained as an engineer, working in 1904 on the Lobito/Benguela railway line in Angola. From there he went to Kenya where he contracted blackwater fever and moved to South Africa to recuperate. While recuperating, he camped with H.J. Raubenheimer an attorney in George and helped to lay out the Fairy Knowe Hotel. In 1921 in conjunction they formed The Wilderness 1921 Ltd. Co. which developed the Wilderness Estate, and later built the Wilderness Hotel. In 1956 he sold his shareholding and his interest in the Wilderness and turned back to Plettenberg Bay where he lived and developed the Sanctuary. He promoted Tourism in the Southern Cape, and laid down the landing strip here

In 1946 Grant had sold his controlling shares in The Beacon Islet (Pty.) Co. Ltd to Baron Ulrich Eugene Behr. My memories of this time is seeing the tall stately Baron dressed in jacket and trousers sitting in the beach watching his rather masculine wife swimming! After one year the Baron sold his shares to a Mr. Cohen of East London. I was with my parents at the time when Cohen announced he would have a deep yacht anchored in the Bay, etc. But nothing came of it and he had to sell his shares to a Mr. Pullen, a farmer from Oudtshoorn district who held them for a few months only. With the other shareholders’ consent he sold them to an Englishman, Mr. Wilson, for £90,000. In 1948 Wilson paid out all the shareholders and formed his own Company. After three years Wilson sold the Company to General Mining for £150,000. They in turn sold the Island to Solly Orenstein for £90,000 when my father became once again a Director together with Mr. J. Prentice. At that time the hotel was most successfully managed by Brian Taylor and his wife. They were particularly kind to my parents, as was the Head Waiter McKenzie, perhaps because they each had good Scottish surnames. McKenzie was from the Transkei and my father, from Inverness. Orenstein subsequently sold Beacon Island hotel to the Southern Sun Hotel Group. Grant’s hotel was demolished to make way for the present structure designed by Andre Hoffe and opened in December 1972. Although the modern building is so constructed as to leave a larger part of Beacon Island in its natural state I personally still miss the older hotel with its memories.