The Van Reenens of Knysna

SPEAKER: Garth van Reenen

The ancestor of the family was the noble Graaf Jacob Van Reenen of Memel in what was then Prussia, who came to the Cape in 1721 in a sturdy little ship, the Astria. His brother Daniel was the Mayor of Allenburg in Prussia and it is said that he had to flee from his country because he took part in a duel, which in those days was strongly forbidden in Germany. And to crown everything, he had unfortunately killed his opponent. The archives show an investigation by the Prussian Government confirming proof of ownership of a large tract of land by the Van Reenen Family in Prussia, but the descendants of Jacob Van Reenen in South Africa never tried to claim those rights.

My great grandfather, Pieter Joseph Vink van Reenen, was born in 1877. He was therefore old enough to become involved in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899/1902. The family was not anti-British in their sentiments and up-bringing, and, in fact, English was their home language. In addition, he had so many friends and relatives involved on both sides of the conflict.

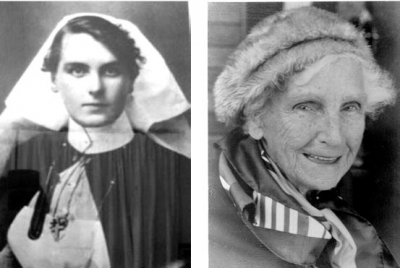

Before she had met my great-grandfather, on the other hand, my great-grandmother became involved in the war as a nurse on the British side. She had been born Florence Eleanor Cross an in Dunedin, New Zealand in 1878. Born of a Scottish father and a mother called Elizabeth of Irish descent, she was known to all as “Tottie”.

My great-grandmother’s father, Edmund Willoughby Cross, was born in Scotland in 1845 and emigrated to New Zealand as a young man.

A mining engineer by profession, he had been subpoenaed to give evidence in a court case in the Transvaal, involving the cyanide process of extracting gold from the gold-bearing quartz which had then recently been discovered in considerable quantities on the Witwatersrand. This visit resulted in him returning to New Zealand, collecting his family, and settling them in Cape Town, before returning to his mining adventures.

Having already been trained as a nurse in New Zealand, my great-grandmother served the British forces in the Anglo-Boer War while based in Cape Town. She served in various institutions, such as the Simons Town Military and Naval Hospital, and the Victoria Cottage Hospital in Wynberg, Cape.

It was while she was there that she became friendly with many of the Cape families. Cape Town was a much smaller place in those days, and getting to know people then was much easier than now. She became very friendly, through her nursing, with a Dr Claude Wright and his family and also the Bisset family, both well known in the social world of the Cape. It was through such friends that she eventually met the Van Reenen family, and eventually married my great-grandfather in 1904.

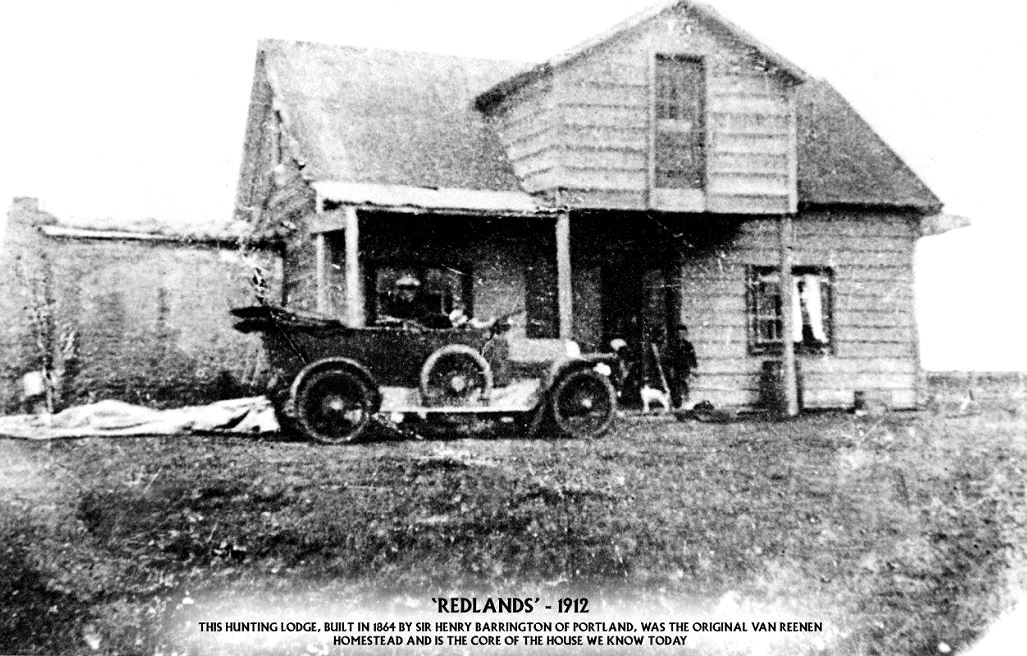

Farming at Redlands

Although my great-grandfather served in various departments of the old Cape Civil Service and did quite well, he yearned to go farming. Finance was, of course, the problem and the country was going through a difficult time as a result of the ravages of the Anglo-Boer War, but the opportunity came about at the time of the Union in May 1910. Prior to the Union, each province had its own network of civil servants and the four provinces had acted quite separately. When Union became an accomplished fact, the civil services were merged into a single unit and my great-grandfather was able to acquire a pension at the early age of 34. A joint pension scheme, it amounted to £9.19.7 per month, and continued to pay my great-grandmother until her death in 1976. Thus the pension went on for 66 years.

My great grandfather decided to join forces with his first cousin, Pieter J. Dormell, who was then still an official in the Forestry Department. Dormell would not take an active part in the farming venture other than to be responsible for his share of the capital to get the scheme going and the partnership was to last for ten years.

The question was where to farm? The Western Cape was more established and more expensive. They even thought of farming in Kenya for reasons which are still unclear as neither of them had ever been there. Dormell had spent his honeymoon in Knysna and the area appealed to him. The property decided upon was originally known as a portion of “Roodekraal”, but either the Hon. Barrington or Mrs Maurice had renamed it “Redlands”, of which the village of Barrington then formed a part.

The move took place in 1912 via train from Cape Town via George and included some livestock: a pedigreed bull, some brood mares, and an expensive pedigreed donkey called “Jack”.

From George they came with a regular horse-drawn post cart along the Seven Passes

Road which is now a National Monument designed to preserve the several historic old bridges which date back to the Victorian Era. The post cart comprised a coach and four to six horses, while the coach man had a bugle which he blew near the corner in the passes to warn any slow-moving ox-wagons to make way for His Majesty’s Royal Mail.

All sorts of farming were tried at Redlands without much success – from wheat, orchards, sheep, pigs and livestock. My great grandfather was a conscientious farmer and he raised some very good crops, but marketing was difficult. There were no marketing control boards so that prices were subject to violent fluctuations, and often the crops could not be sold in the limited markets that were available in the area.

The Redlands house had been built originally for the Hon. Henry Barrington by a Norwegian named Franzen. The design had followed that of traditional Norwegian wooden houses, but the house was little more than a shack and was built to serve as a shooting box. When the Van Reenens first came to Redlands, the Hon. Barrington had been dead for some time and the house had squatters living in it, so it was run down and was in a poor state of repair. The house had a pigsty attached to the then back door. Tottie refused to stay there until it had been removed and made “live-able”. The furniture was very basic: consisting of a single wicker chair and paraffin packing cases for cupboards. Bathing facilities as we know them were non-existent and they had to make use of tin baths.

A Mrs Gabriella Stuart, a daughter of the Hon. Barrington, was a widow who was asked to go and live at Redlands and be the governess to the three Van Reenen children. Although she agreed, it soon became apparent that she knew nothing about teaching. My great-uncle Vincent remembers Mrs Stuart telling them that she dreaded being buried alive and had given special instructions to her doctor to make doubly sure by rather grisly means that she was indeed quiet dead.

Rheenendal

It was in 1920 that the Van Reenen Family purchased the “Rheenendal” farm. Registration of the farm was due to be made at the Deeds Office in Cape Town, as it was necessary for the farm to have its own name. For some obscure reason the solicitors must have decided on their

own initiative to name the farm “Fescue Meadows” – “fescue” being the name of a particular species of fodder. Why they should have chosen this name is unknown. There certainly was no fescue grass on the property. Our family remembers the story that a telegram had brought the news that the property was about to be registered and that the name “Fescue Meadows” had been suggested. Since the family back then did not approve of this inappropriate name, it was Tottie who suggested that the farm be named “Rheenendal”, in recognition of both the family name, and the ancestral home of Rheenen in Holland.

When Mr P.J. Van Reenen, Snr. was able to take occupation , he started farming operations there and commuted between “Redlands” and “Rheenendal”, sometimes on horseback, other times by bicycle, but mostly on foot. He claimed that this slower mode of transport, as compared with using a Cape cart, enabled him to think and try to sort out the many problems that confronted him at that time. The story is told that once, when using the bicycle, he was so deep in thought that when he got to the Klein Homtini he dismounted and went towards the water, thinking for a moment that he was on horseback, to give his “horse” a drink.

The Sawmill Industry in Rheenendal

Boekenhout, or Cape Beech, was estimated to have a value of 100,000 pounds on the property: attractive timber from a grain point-of-view but at that time there had been no demand as it was so soft. In order to generate cash from the forest, therefore, my great-grandfather employed some woodcutters on a share basis. The timber produced mainly spokes, felloes and ironwood wagon parts which were then sold to timber merchants in Knysna. These wagon parts were taken down from Rheenendal to Knysna town with the P.J. Van Reenen French Dewald Lorry purchased in 1928. The lorry was powered and driven by producer gas. It had a hopper attached on the driver’s side and into this wood chips would be fed. The initial start-up was on petrol and as soon as the producer unit was burning well, and gas was being produced the engine would be coaxed over to the gas, and the petrol switched off. It became quite a feature driving through the streets of Knysna. The Lorry had solid rubber wheels so that the ride on the corrugated, potholed roads, was by no means comfortable but at least there were no stops for punctures. At that time the main buyers were Thesen & Parkes who virtually had the monopoly and could regulate prices accordingly. So it was decided to start processing timber for themselves and hence the start of the Sawmilling industry in Rheenendal. The Sawmill started in August 1921.

The General Dealer & Butcher Shop

Since its inception in the early 1920s, “The Shop”, as it is generally referred to, had played an important, albeit unobtrusive, part in the development of our business, and as such justifies a short description of its progress and development.

Initially, when my great-grandmother first took over the shop, it was situated in what previously had been a storeroom behind the Rheenendal farm house. Some intervening walls in the storeroom were knocked out, shelves were put in, and a counter erected, and that then comprised the shop.

Later, a little section was cordoned off to become the so-called butchery. My great-grandmother was still doing the clerical work of the business and the shop was only opened when the odd customer came along. The mill and farm workers were given advances in the way of food, so the weekends in the shop were usually quite busy and there were no set hours. The woodcutters in Millwood were also “on the book” for basic needs, such as flower, sugar, and coffee. They were only paid at the end of the month and at 5 p.m. on the last day of the month, they would venture down to Rheenendal to pay their accounts and start afresh.

In later years, “The Shop” was moved to its present position, where eventually it became the base of the P.J. Van Reenen offices, General Dealer, Stinkwood Furniture Showroom, and eventually a Petrol Station, an ideal location, since it was on the Seven Passes Road. We were further granted a Postal Agency, for which the Government paid us £3 a month.

“The Shop” meanwhile went on and business gradually increased. The next step in the march of progress was the purchase of our first typewriter. Vintcent van Rooyen remarks that it is “Hardly a matter to record these days, but then it seemed to us that any concern that might own a typewriter was really going places. I remember it was a second-hand Remington, which we bought through an advertisement for a couple of pounds. It served us many years, but initially the problem was that nobody knew how to operate the thing. So, it having devolved upon me to fathom the intricacies, in due course I became quite a proficient two-finger typist, a skill in which I have never developed further, even though I have had to do all the typing for a number of years.”

Garth then went on to describe the latest exciting developments at the restaurant of “Totties” on the Rheenendal road, as well as all the developments in the surrounding area, including the rebirth of the Gold Mining Village as a tourist destination.